As the South African building materials market has become more diverse and competitive, manufacturers have jostled to provide the longest warranty terms to entice buyers. Though new technologies and materials are undoubtedly improving product performance in leaps and bounds, warranties should not all be taken at face value and customers should take the time to scrutinise what is really being offered.

By definition, a warranty is a written guarantee for a defined period, issued by the manufacturer, that is a promise to repair or replace a product purchased by the customer, if the product fails to live up to specified performance.

Defining specified performance is the crux of the problem with many fundamentally flawed warranties, says Nathan Chapman, co-founder of building materials group Eva-Last. “The warranty is an important document for several reasons. First, it should set out how to use the product and how not to use it. Second, it should clearly define under which circumstances replacement or repair will take place and how the customer engages with that process.”

In recognising a sound warranty from an effectively empty promise, Chapman says the first thing to look out for is vagueness.

“A good warranty is detailed and explicit. It tells you what you are covered for in terms of latent defects, what is not covered, how long the coverage lasts, the value proportion the customer may recover as time passes and the steps to take for that recovery.”

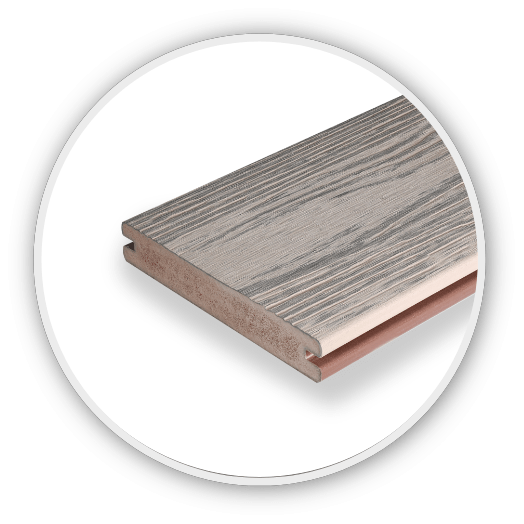

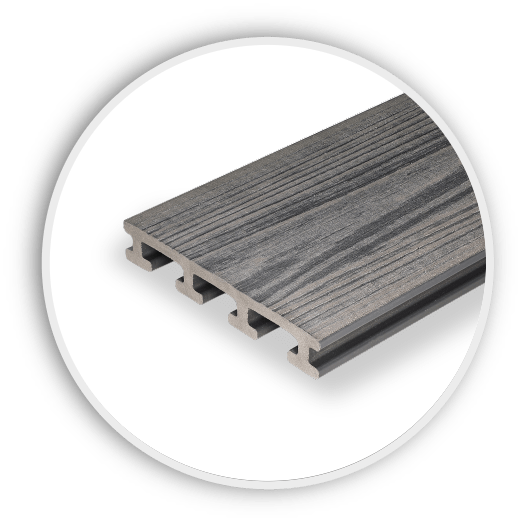

A cursory investigation of some warranties offered on composite decking and cladding materials shows that certain manufacturers active in South Africa lack any specificity in their warranty description. “Where many customers get caught out is with a warranty that is constructed to leave any recovery of value or replacement up to the discretion of the manufacturer. This can cause many problems where the manufacturer is either unwilling or under-resourced in our territory to make good on a warranty claim,” says Chapman.

On the other hand, Chapman says Eva-Last’s products are warranted against colour fade in a completely objective way. “Our threshold for recovery is Delta E greater than 5. That is a standard, quantifiable and objective measure between the original warranted colour and the colour of a potentially defective product.

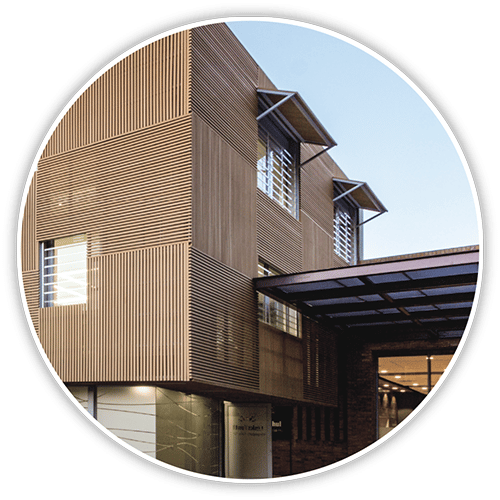

“In an outdoor installation, where there are so many variables, you want to see a warranty that takes them all into account. A detailed and comprehensive warranty shows that the manufacturer has taken the time to test its products and has established a benchmark for the fundamental expected performance of each product. In general, these will relate to building codes for that territory,” he says.

Building codes represent another common issue with warranted performance. “Some manufacturers make misleading statements about testing, standards and compliance. A test result from one of the many testing agencies is not the same as being compliant with local building standards. A manufacturer cannot be compliant with a testing body,” Chapman explains.

Any robust warranty will allow for a claim against a proportion of value on a defective product, however many customers are also surprised by the concept of fair use that determines recovery rates. Chapman says while a good warranty will naturally allow a customer to reclaim 100% of the original cost of the product in the first few years of the product’s lifespan, it is reasonable to expect that as years pass, customers will not reclaim the full value of replacement materials.

“Once ten years or more have passed, it may be that either the originally installed product is no longer available in the manufacturer’s catalogue, or the replacement product is now more expensive as a result of inflation. Just as with other consumer goods, replacement value will drop off over time.” But, no matter what time period has elapsed, a warranty should be simple and easy to enact.

“An intentional warranty should also clearly define the user’s responsibilities for aspects such as cleaning and care, and therefore it would be unreasonable to expect a successful claim where the owner of the product has been negligent, as with any warrantied products from electronics to vehicles” says Chapman.

In general, building materials should be warranted against latent defects not brought about by fair and expected use conditions. For example, a composite deck will shrug off spills of substances commonly expected to be used on or around them – such as foodstuffs and beverages from a braai – but should not be expected to deal with unusual substances like chemicals or long-term spillages that the owner has not attended to in a reasonable time period.

“Given that a good warranty clearly spells out expected use conditions, the manufacturer should then commit to recovery or replacement of defective materials with a minimum of fuss,” says Chapman.

Property buyers who may inherit an installed deck, for example, may be surprised when they try to enact a warranty as the second owner. “It is not uncommon for manufacturers to insist on registering as the owner of a product, and to then reject warranty claims from subsequent owners who did not know about the registration requirement and do not have proof of purchase. A good warranty will continue to hold for an identifiable installed product, no matter who owns it – provided it was installed correctly and has been properly maintained,” Chapman says.

A good building materials warranty is a supportive document that is meant to provide peace of mind and protect the customers investment. “With the range of product choices available on the market today, it is important to realise that the warranty’s specs are just as important as the specs of a product itself. Just as product innovation has developed and improved over time, so have the majority of warranties, and we are proud to offer some market-leading warranties. Customers stand to benefit, so they should take advantage of the best terms available,” says Chapman.